The Plethodontidae, or lungless salamanders, are a family of salamanders. Most species are native to the Western Hemisphere, from British Columbia to Brazil, although a few species are found in Sardinia, Europe south of the Alps, and South Korea. In terms of number of species, they are by far the largest group of salamanders.

The Plethodontidae, or lungless salamanders, are a family of salamanders. Most species are native to the Western Hemisphere, from British Columbia to Brazil, although a few species are found in Sardinia, Europe south of the Alps, and South Korea. In terms of number of species, they are by far the largest group of salamanders.

The Plethodontidae, or lungless salamanders, are a family of salamanders. Most species are native to the Western Hemisphere, from British Columbia to Brazil, although a few species are found in Sardinia, Europe south of the Alps, and South Korea. In terms of number of species, they are by far the largest group of salamanders.

The Plethodontidae, or lungless salamanders, are a family of salamanders. Most species are native to the Western Hemisphere, from British Columbia to Brazil, although a few species are found in Sardinia, Europe south of the Alps, and South Korea. In terms of number of species, they are by far the largest group of salamanders.

The Plethodontidae, or lungless salamanders, are a family of salamanders. Most species are native to the Western Hemisphere, from British Columbia to Brazil, although a few species are found in Sardinia, Europe south of the Alps, and South Korea. In terms of number of species, they are by far the largest group of salamanders.

Cestoda (Cestoidea) is a class of parasitic worms of the flatworm(Platyhelminthes) phylum. They are informally referred to as cestodes. The best-known species are commonly called tapeworms. All cestodes are parasitic and their life histories vary, but typically they live in the digestive tracts of vertebrates as adults, and often in the bodies of other species of animals as juveniles. Over a thousand species have been described, and all vertebrate species may be parasitised by at least one species of tapeworm.

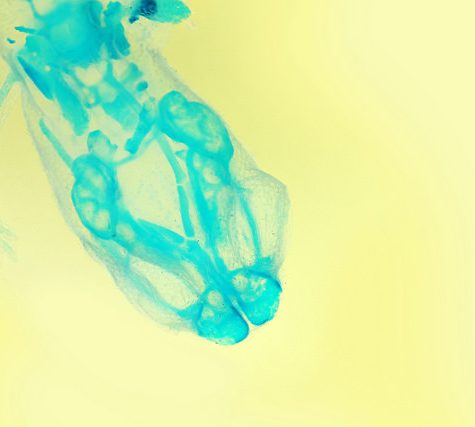

Tapeworm Theme: Research by Jimmy Bernot and Dr. Janine Caira

Researchers in Dr. Janine Caira’s lab at UConn study tapeworms: the ribbon-like parasites found in the intestine of all major groups of vertebrates. The Caira lab primarily studies tapeworms from sharks, skates, and stingrays, which host a diverse assortment of tapeworms. We are interested in how these tapeworms are related, how they evolve, and the dynamic interactions they have with their hosts over time.

It may seem rare or even shocking to discover a new species, but in the Caira lab numerous new species of tapeworms are discovered and described just about every year! In fact, the tapeworms photographed here by Mark Smith were discovered by the Caira lab in our very own back yard — Long Island Sound. This species is found in the intestine of a common shark, Mustelus canis, often called the smoothdog fish, which may be familiar to recreational fisherman in the Northeastern U.S. In fact, if you have ever caught a smoothdog fish, it is likely that the tapeworm species pictured here was inside the shark you caught, just waiting to be discovered!

One of the main goals of my Master’s thesis was to understand how this species remains attached to the intestine of its shark host. This is of the utmost importance to these worms because they cannot survive outside of the their host’s intestine. These photographs where taken to better understand the way these tapeworms maintain this intimate relationship.

In these close-up images of its scolex (think of it as the tapeworm equivalent of a head, yet strangely lacking eyes, ears, a nose and a mouth) you can see many of the specialized structures like hooks, muscular flaps, and suckers that enable this worm to remain securely anchored to its host. If you look along its ribbon-like body, you can see serrated edges characteristic of this tapeworm and its relatives.

In these photographs you can see tapeworms attached to the intestine of a shark. These photographs have helped us understand that the serrated margins of these worms help secure the worm to its host by locking into small surface features of the intestine like dovetail joints — something never before shown — demonstrating the functionality of these previously mysterious structures.

Together, these photographs help us better understand the way these worms live their bizarre lives in the dark, complex, and shifting environment of a shark intestine.

Cestoda (Cestoidea) is a class of parasitic worms of the flatworm(Platyhelminthes) phylum. They are informally referred to as cestodes. The best-known species are commonly called tapeworms. All cestodes are parasitic and their life histories vary, but typically they live in the digestive tracts of vertebrates as adults, and often in the bodies of other species of animals as juveniles. Over a thousand species have been described, and all vertebrate species may be parasitised by at least one species of tapeworm.

Tapeworm Theme: Research by Jimmy Bernot and Dr. Janine Caira

Researchers in Dr. Janine Caira’s lab at UConn study tapeworms: the ribbon-like parasites found in the intestine of all major groups of vertebrates. The Caira lab primarily studies tapeworms from sharks, skates, and stingrays, which host a diverse assortment of tapeworms. We are interested in how these tapeworms are related, how they evolve, and the dynamic interactions they have with their hosts over time.

It may seem rare or even shocking to discover a new species, but in the Caira lab numerous new species of tapeworms are discovered and described just about every year! In fact, the tapeworms photographed here by Mark Smith were discovered by the Caira lab in our very own back yard — Long Island Sound. This species is found in the intestine of a common shark, Mustelus canis, often called the smoothdog fish, which may be familiar to recreational fisherman in the Northeastern U.S. In fact, if you have ever caught a smoothdog fish, it is likely that the tapeworm species pictured here was inside the shark you caught, just waiting to be discovered!

One of the main goals of my Master’s thesis was to understand how this species remains attached to the intestine of its shark host. This is of the utmost importance to these worms because they cannot survive outside of the their host’s intestine. These photographs where taken to better understand the way these tapeworms maintain this intimate relationship.

In these close-up images of its scolex (think of it as the tapeworm equivalent of a head, yet strangely lacking eyes, ears, a nose and a mouth) you can see many of the specialized structures like hooks, muscular flaps, and suckers that enable this worm to remain securely anchored to its host. If you look along its ribbon-like body, you can see serrated edges characteristic of this tapeworm and its relatives.

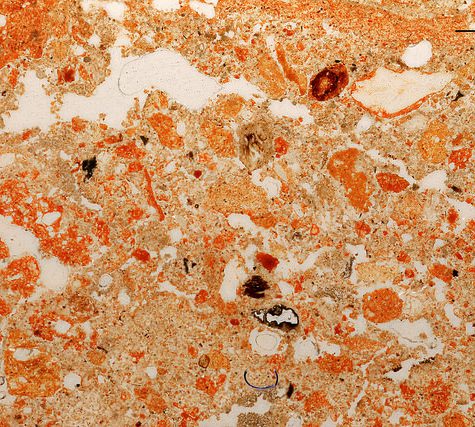

In these photographs you can see tapeworms attached to the intestine of a shark. These photographs have helped us understand that the serrated margins of these worms help secure the worm to its host by locking into small surface features of the intestine like dovetail joints — something never before shown — demonstrating the functionality of these previously mysterious structures.

Together, these photographs help us better understand the way these worms live their bizarre lives in the dark, complex, and shifting environment of a shark intestine.

Cestoda (Cestoidea) is a class of parasitic worms of the flatworm(Platyhelminthes) phylum. They are informally referred to as cestodes. The best-known species are commonly called tapeworms. All cestodes are parasitic and their life histories vary, but typically they live in the digestive tracts of vertebrates as adults, and often in the bodies of other species of animals as juveniles. Over a thousand species have been described, and all vertebrate species may be parasitised by at least one species of tapeworm.

Tapeworm Theme: Research by Jimmy Bernot and Dr. Janine Caira

Researchers in Dr. Janine Caira’s lab at UConn study tapeworms: the ribbon-like parasites found in the intestine of all major groups of vertebrates. The Caira lab primarily studies tapeworms from sharks, skates, and stingrays, which host a diverse assortment of tapeworms. We are interested in how these tapeworms are related, how they evolve, and the dynamic interactions they have with their hosts over time.

It may seem rare or even shocking to discover a new species, but in the Caira lab numerous new species of tapeworms are discovered and described just about every year! In fact, the tapeworms photographed here by Mark Smith were discovered by the Caira lab in our very own back yard — Long Island Sound. This species is found in the intestine of a common shark, Mustelus canis, often called the smoothdog fish, which may be familiar to recreational fisherman in the Northeastern U.S. In fact, if you have ever caught a smoothdog fish, it is likely that the tapeworm species pictured here was inside the shark you caught, just waiting to be discovered!

One of the main goals of my Master’s thesis was to understand how this species remains attached to the intestine of its shark host. This is of the utmost importance to these worms because they cannot survive outside of the their host’s intestine. These photographs where taken to better understand the way these tapeworms maintain this intimate relationship.

In these close-up images of its scolex (think of it as the tapeworm equivalent of a head, yet strangely lacking eyes, ears, a nose and a mouth) you can see many of the specialized structures like hooks, muscular flaps, and suckers that enable this worm to remain securely anchored to its host. If you look along its ribbon-like body, you can see serrated edges characteristic of this tapeworm and its relatives.

In these photographs you can see tapeworms attached to the intestine of a shark. These photographs have helped us understand that the serrated margins of these worms help secure the worm to its host by locking into small surface features of the intestine like dovetail joints — something never before shown — demonstrating the functionality of these previously mysterious structures.

Together, these photographs help us better understand the way these worms live their bizarre lives in the dark, complex, and shifting environment of a shark intestine.

Cestoda (Cestoidea) is a class of parasitic worms of the flatworm(Platyhelminthes) phylum. They are informally referred to as cestodes. The best-known species are commonly called tapeworms. All cestodes are parasitic and their life histories vary, but typically they live in the digestive tracts of vertebrates as adults, and often in the bodies of other species of animals as juveniles. Over a thousand species have been described, and all vertebrate species may be parasitised by at least one species of tapeworm.

Tapeworm Theme: Research by Jimmy Bernot and Dr. Janine Caira

Researchers in Dr. Janine Caira’s lab at UConn study tapeworms: the ribbon-like parasites found in the intestine of all major groups of vertebrates. The Caira lab primarily studies tapeworms from sharks, skates, and stingrays, which host a diverse assortment of tapeworms. We are interested in how these tapeworms are related, how they evolve, and the dynamic interactions they have with their hosts over time.

It may seem rare or even shocking to discover a new species, but in the Caira lab numerous new species of tapeworms are discovered and described just about every year! In fact, the tapeworms photographed here by Mark Smith were discovered by the Caira lab in our very own back yard — Long Island Sound. This species is found in the intestine of a common shark, Mustelus canis, often called the smoothdog fish, which may be familiar to recreational fisherman in the Northeastern U.S. In fact, if you have ever caught a smoothdog fish, it is likely that the tapeworm species pictured here was inside the shark you caught, just waiting to be discovered!

One of the main goals of my Master’s thesis was to understand how this species remains attached to the intestine of its shark host. This is of the utmost importance to these worms because they cannot survive outside of the their host’s intestine. These photographs where taken to better understand the way these tapeworms maintain this intimate relationship.

In these close-up images of its scolex (think of it as the tapeworm equivalent of a head, yet strangely lacking eyes, ears, a nose and a mouth) you can see many of the specialized structures like hooks, muscular flaps, and suckers that enable this worm to remain securely anchored to its host. If you look along its ribbon-like body, you can see serrated edges characteristic of this tapeworm and its relatives.

In these photographs you can see tapeworms attached to the intestine of a shark. These photographs have helped us understand that the serrated margins of these worms help secure the worm to its host by locking into small surface features of the intestine like dovetail joints — something never before shown — demonstrating the functionality of these previously mysterious structures.

Together, these photographs help us better understand the way these worms live their bizarre lives in the dark, complex, and shifting environment of a shark intestine.

Cestoda (Cestoidea) is a class of parasitic worms of the flatworm(Platyhelminthes) phylum. They are informally referred to as cestodes. The best-known species are commonly called tapeworms. All cestodes are parasitic and their life histories vary, but typically they live in the digestive tracts of vertebrates as adults, and often in the bodies of other species of animals as juveniles. Over a thousand species have been described, and all vertebrate species may be parasitised by at least one species of tapeworm.

Tapeworm Theme: Research by Jimmy Bernot and Dr. Janine Caira

Researchers in Dr. Janine Caira’s lab at UConn study tapeworms: the ribbon-like parasites found in the intestine of all major groups of vertebrates. The Caira lab primarily studies tapeworms from sharks, skates, and stingrays, which host a diverse assortment of tapeworms. We are interested in how these tapeworms are related, how they evolve, and the dynamic interactions they have with their hosts over time.

It may seem rare or even shocking to discover a new species, but in the Caira lab numerous new species of tapeworms are discovered and described just about every year! In fact, the tapeworms photographed here by Mark Smith were discovered by the Caira lab in our very own back yard — Long Island Sound. This species is found in the intestine of a common shark, Mustelus canis, often called the smoothdog fish, which may be familiar to recreational fisherman in the Northeastern U.S. In fact, if you have ever caught a smoothdog fish, it is likely that the tapeworm species pictured here was inside the shark you caught, just waiting to be discovered!

One of the main goals of my Master’s thesis was to understand how this species remains attached to the intestine of its shark host. This is of the utmost importance to these worms because they cannot survive outside of the their host’s intestine. These photographs where taken to better understand the way these tapeworms maintain this intimate relationship.

In these close-up images of its scolex (think of it as the tapeworm equivalent of a head, yet strangely lacking eyes, ears, a nose and a mouth) you can see many of the specialized structures like hooks, muscular flaps, and suckers that enable this worm to remain securely anchored to its host. If you look along its ribbon-like body, you can see serrated edges characteristic of this tapeworm and its relatives.

In these photographs you can see tapeworms attached to the intestine of a shark. These photographs have helped us understand that the serrated margins of these worms help secure the worm to its host by locking into small surface features of the intestine like dovetail joints — something never before shown — demonstrating the functionality of these previously mysterious structures.

Together, these photographs help us better understand the way these worms live their bizarre lives in the dark, complex, and shifting environment of a shark intestine.

Clay is a finely-grained natural rock or soil material that combines one or more clay minerals with traces of metal oxides and organic matter. Geologic clay deposits are mostly composed of phyllosilicate minerals containing variable amounts of water trapped in the mineral structure. Clays are plastic due to their water content and become hard, brittle and non–plastic upon drying or firing.[1][2][3] Depending on the soil’s content in which it is found, clay can appear in various colours from white to dull grey or brown to deep orange-red.

Cheetos (formerly styled as Chee-tos until 1998) is a brand of cheese-flavored, puffed cornmeal snacks made by Frito-Lay, a subsidiary of PepsiCo. Fritos creator Charles Elmer Doolin invented Cheetos in 1948, and began national distribution in the U.S. The initial success of Cheetos was a contributing factor to the merger between The Frito Company and H.W. Lay & Company in 1961 to form Frito-Lay. In 1965 Frito-Lay became a subsidiary of The Pepsi-Cola Company, forming PepsiCo, the current owner of the Cheetos brand.

Kit Kat is a chocolate-covered wafer bar confection created by Rowntree’s of York, United Kingdom, and is now produced globally by Nestlé, which acquired Rowntree in 1988,[1] with the exception of the United States where it is made under license by H.B. Reese Candy Company, a division of The Hershey Company. The standard bars consist of two or four fingers composed of three layers of wafer, separated and covered by an outer layer of chocolate. Each finger can be snapped from the bar separately. There are many different flavours of Kit Kat.

Kit Kat is a chocolate-covered wafer bar confection created by Rowntree’s of York, United Kingdom, and is now produced globally by Nestlé, which acquired Rowntree in 1988,[1] with the exception of the United States where it is made under license by H.B. Reese Candy Company, a division of The Hershey Company. The standard bars consist of two or four fingers composed of three layers of wafer, separated and covered by an outer layer of chocolate. Each finger can be snapped from the bar separately. There are many different flavours of Kit Kat.

Kit Kat is a chocolate-covered wafer bar confection created by Rowntree’s of York, United Kingdom, and is now produced globally by Nestlé, which acquired Rowntree in 1988,[1] with the exception of the United States where it is made under license by H.B. Reese Candy Company, a division of The Hershey Company. The standard bars consist of two or four fingers composed of three layers of wafer, separated and covered by an outer layer of chocolate. Each finger can be snapped from the bar separately. There are many different flavours of Kit Kat.

A hard candy, or boiled sweet, is a sugar candy prepared from one or more sugar-based syrups that is boiled to a temperature of 160 °C (320 °F) to make candy. Among the many hard candy varieties are stick candy (such as the candy cane), lollipops, aniseed twists, and bêtises de Cambrai.

Hard candy is nearly 100% sugar by weight; Recipes for hard candy may use syrups of sucrose, glucose, fructose or other sugars. Sugar-free versions have also been created.

L Plate for Mounting Specimens on Translational Stage

L Plate for Mounting Specimens on Translational Stage Diffuser for Canon RF 100mm Macro

Diffuser for Canon RF 100mm Macro Camera Err 20 or Err 30 Service and Repair

Camera Err 20 or Err 30 Service and Repair Fluorescence Kit

Fluorescence Kit Premium Training & Support

Premium Training & Support Diffuser for Canon M-PE 65mm 1-5x

Diffuser for Canon M-PE 65mm 1-5x Mitutoyo to 77mm Adapter

Mitutoyo to 77mm Adapter Diffuser for Mitutoyo M Plan APO Objectives

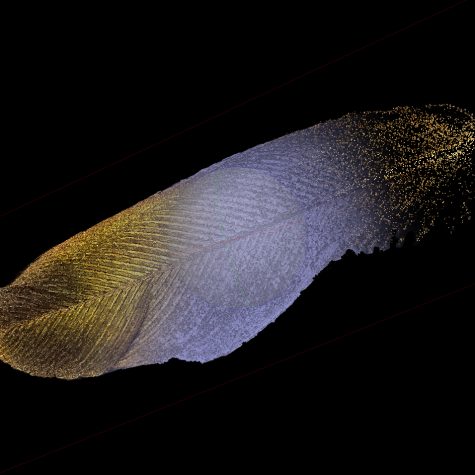

Diffuser for Mitutoyo M Plan APO Objectives Ruby-throated Hummingbird Tail Feather: 3D Model

Ruby-throated Hummingbird Tail Feather: 3D Model