Kit Kat is a chocolate-covered wafer bar confection created by Rowntree’s of York, United Kingdom, and is now produced globally by Nestlé, which acquired Rowntree in 1988,[1] with the exception of the United States where it is made under license by H.B. Reese Candy Company, a division of The Hershey Company. The standard bars consist of two or four fingers composed of three layers of wafer, separated and covered by an outer layer of chocolate. Each finger can be snapped from the bar separately. There are many different flavours of Kit Kat.

A hard candy, or boiled sweet, is a sugar candy prepared from one or more sugar-based syrups that is boiled to a temperature of 160 °C (320 °F) to make candy. Among the many hard candy varieties are stick candy (such as the candy cane), lollipops, aniseed twists, and bêtises de Cambrai.

Hard candy is nearly 100% sugar by weight; Recipes for hard candy may use syrups of sucrose, glucose, fructose or other sugars. Sugar-free versions have also been created.

Popcorn is a variety of corn kernel, which forcefully expands and puffs up when heated.

A popcorn kernel’s strong hull contains the seed’s hard, starchy endosperm with 14-20% moisture, which turns to steam as the kernel is heated. The pressure continues building until it exceeds the hull’s ability to contain it. The kernel ruptures and forcefully expands, allowing the contents to expand, cool, and finally set in a popcorn puff 2 to 5 times the size of the original kernel.[1]

The orange is the fruit of the citrus species Citrus × sinensis in the family Rutaceae.[1] It is also called sweet orange, to distinguish it from the related Citrus × aurantium, referred to as bitter orange. The sweet orange reproduces asexually (apomixis through nucellar embryony); varieties of sweet orange arise through mutations.[2]

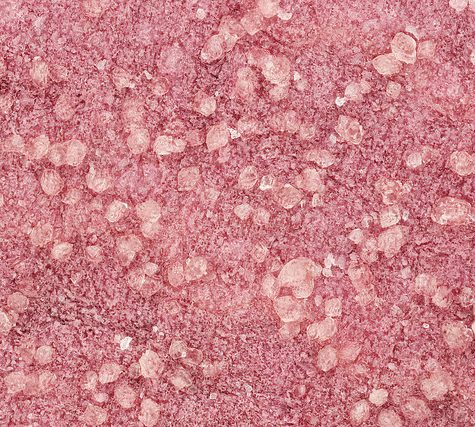

Salt and pepper is the common name for edible salt and black pepper, a traditionally paired set of condiments found on dining tables where European-style food is eaten. The pairing of salt and pepper as table condiments dates to seventeenth-century French cuisine, which considered pepper the only spice (as distinct from herbs such as fines herbes) which did not overpower the true taste of food.[1] They are typically found in a set of salt and pepper shakers, often a matched set; however, salt and pepper are typically maintained in separate shakers.

The banana is an edible fruit – botanically a berry[1][2] – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus Musa.[3] In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called plantains, in contrast to dessert bananas. The fruit is variable in size, color and firmness, but is usually elongated and curved, with soft flesh rich in starchcovered with a rind which may be green, yellow, red, purple, or brown when ripe. The fruits grow in clusters hanging from the top of the plant. Almost all modern edible parthenocarpic(seedless) bananas come from two wild species – Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. The scientific names of most cultivated bananas are Musa acuminata, Musa balbisiana, and Musa × paradisiaca for the hybrid Musa acuminata × M. balbisiana, depending on their genomic constitution. The old scientific name Musa sapientum is no longer used.

The banana is an edible fruit – botanically a berry[1][2] – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus Musa.[3] In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called plantains, in contrast to dessert bananas. The fruit is variable in size, color and firmness, but is usually elongated and curved, with soft flesh rich in starchcovered with a rind which may be green, yellow, red, purple, or brown when ripe. The fruits grow in clusters hanging from the top of the plant. Almost all modern edible parthenocarpic(seedless) bananas come from two wild species – Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. The scientific names of most cultivated bananas are Musa acuminata, Musa balbisiana, and Musa × paradisiaca for the hybrid Musa acuminata × M. balbisiana, depending on their genomic constitution. The old scientific name Musa sapientum is no longer used.

The banana is an edible fruit – botanically a berry[1][2] – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus Musa.[3] In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called plantains, in contrast to dessert bananas. The fruit is variable in size, color and firmness, but is usually elongated and curved, with soft flesh rich in starchcovered with a rind which may be green, yellow, red, purple, or brown when ripe. The fruits grow in clusters hanging from the top of the plant. Almost all modern edible parthenocarpic(seedless) bananas come from two wild species – Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. The scientific names of most cultivated bananas are Musa acuminata, Musa balbisiana, and Musa × paradisiaca for the hybrid Musa acuminata × M. balbisiana, depending on their genomic constitution. The old scientific name Musa sapientum is no longer used.

The banana is an edible fruit – botanically a berry[1][2] – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus Musa.[3] In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called plantains, in contrast to dessert bananas. The fruit is variable in size, color and firmness, but is usually elongated and curved, with soft flesh rich in starchcovered with a rind which may be green, yellow, red, purple, or brown when ripe. The fruits grow in clusters hanging from the top of the plant. Almost all modern edible parthenocarpic(seedless) bananas come from two wild species – Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. The scientific names of most cultivated bananas are Musa acuminata, Musa balbisiana, and Musa × paradisiaca for the hybrid Musa acuminata × M. balbisiana, depending on their genomic constitution. The old scientific name Musa sapientum is no longer used.

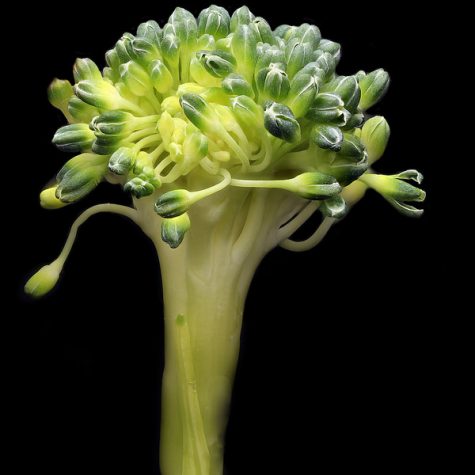

Broccoli is an edible green plant in the cabbage family whose large flowering head is eaten as a vegetable.

The word broccoli comes from the Italian plural of broccolo, which means “the flowering crest of a cabbage“, and is the diminutive form of brocco, meaning “small nail” or “sprout”.[3] Broccoli is often boiled or steamed but may be eaten raw.[4]

Broccoli is classified in the Italica cultivar group of the species Brassica oleracea. Broccoli has large flower heads, usually green in color, arranged in a tree-like structure branching out from a thick, edible stalk. The mass of flower heads is surrounded by leaves. Broccoli resembles cauliflower, which is a different cultivar group of the same species.

Broccoli is a result of careful breeding of cultivated Brassica crops in the northern Mediterranean starting in about the 6th century BC.[5] Since the time of the Roman Empire, broccoli has been considered a uniquely valuable food among Italians.[6]Broccoli was brought to England from Antwerp in the mid-18th century by Peter Scheemakers.[7] Broccoli was first introduced to the United States by Southern Italian immigrants, but did not become widely popular until the 1920s.[8]

Broccoli is an edible green plant in the cabbage family whose large flowering head is eaten as a vegetable.

The word broccoli comes from the Italian plural of broccolo, which means “the flowering crest of a cabbage“, and is the diminutive form of brocco, meaning “small nail” or “sprout”.[3] Broccoli is often boiled or steamed but may be eaten raw.[4]

Broccoli is classified in the Italica cultivar group of the species Brassica oleracea. Broccoli has large flower heads, usually green in color, arranged in a tree-like structure branching out from a thick, edible stalk. The mass of flower heads is surrounded by leaves. Broccoli resembles cauliflower, which is a different cultivar group of the same species.

Broccoli is a result of careful breeding of cultivated Brassica crops in the northern Mediterranean starting in about the 6th century BC.[5] Since the time of the Roman Empire, broccoli has been considered a uniquely valuable food among Italians.[6]Broccoli was brought to England from Antwerp in the mid-18th century by Peter Scheemakers.[7] Broccoli was first introduced to the United States by Southern Italian immigrants, but did not become widely popular until the 1920s.[8]

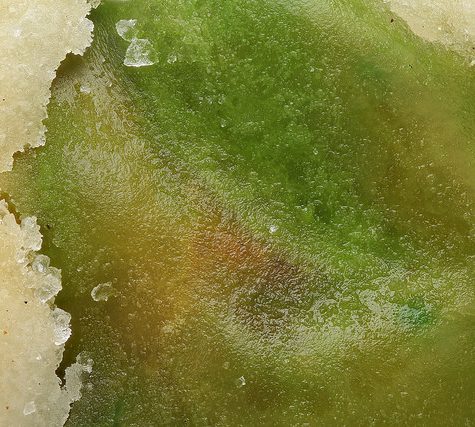

Wasabi (ワサビ or わさび(山葵), earlier 和佐比; Eutrema japonicum or Wasabia japonica)[1] is a plant of the Brassicaceae family, which includes cabbages, horseradish, and mustard. It is also called Japanese horseradish,[2] although horseradish is a different plant (which is generally used as a substitute for wasabi, due to the scarcity of the wasabi plant). Wasabi is generally used as a sauce that makes sushi or other foods more flavorful by adding spice. Its stem is used as a condiment and has an extremely strong pungencymore akin to hot mustard than the capsaicin in a chili pepper, producing vapours that stimulate the nasal passages more than the tongue. The plant grows naturally along stream beds in mountain river valleys in Japan. The two main cultivars in the marketplace are E. japonicum ‘Daruma’ and ‘Mazuma’, but there are many others.[3] The origin of wasabi cuisine has been clarified from the oldest historical records; it takes its rise in Nara prefecture,[4] and more recently has seen a surge in popularity from the early 1990s to mid 2000s.[5]

Wasabi (ワサビ or わさび(山葵), earlier 和佐比; Eutrema japonicum or Wasabia japonica)[1] is a plant of the Brassicaceae family, which includes cabbages, horseradish, and mustard. It is also called Japanese horseradish,[2] although horseradish is a different plant (which is generally used as a substitute for wasabi, due to the scarcity of the wasabi plant). Wasabi is generally used as a sauce that makes sushi or other foods more flavorful by adding spice. Its stem is used as a condiment and has an extremely strong pungencymore akin to hot mustard than the capsaicin in a chili pepper, producing vapours that stimulate the nasal passages more than the tongue. The plant grows naturally along stream beds in mountain river valleys in Japan. The two main cultivars in the marketplace are E. japonicum ‘Daruma’ and ‘Mazuma’, but there are many others.[3] The origin of wasabi cuisine has been clarified from the oldest historical records; it takes its rise in Nara prefecture,[4] and more recently has seen a surge in popularity from the early 1990s to mid 2000s.[5]

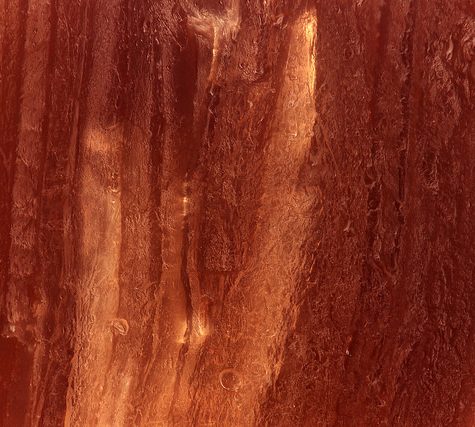

Roast beef is a dish of beef which is roasted in an oven. Essentially prepared as a main meal, the leftovers are often used in sandwiches and sometimes are used to make hash. In the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand and Australia, roast beef is one of the meats traditionally served at Sunday dinner, although it is also often served as a cold cut in delicatessen stores, usually in sandwiches. A traditional side dish to roast beef is Yorkshire pudding.

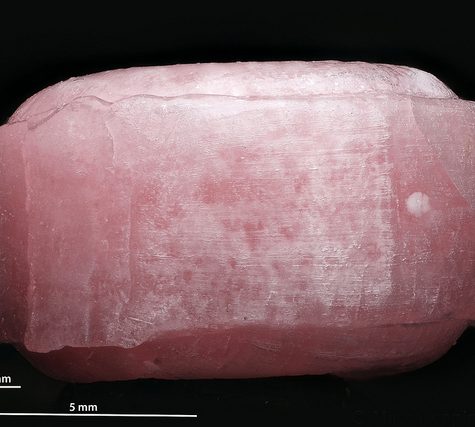

Potassium bitartrate, also known as potassium hydrogen tartrate, with formula KC4H5O6, is a byproduct of winemaking. In cooking it is known as cream of tartar. It is the potassium acid salt of tartaric acid (a carboxylic acid). It can be used in baking or as a cleaning solution (when mixed with an acidic solution such as lemon juice or white vinegar).

Potassium bitartrate, also known as potassium hydrogen tartrate, with formula KC4H5O6, is a byproduct of winemaking. In cooking it is known as cream of tartar. It is the potassium acid salt of tartaric acid (a carboxylic acid). It can be used in baking or as a cleaning solution (when mixed with an acidic solution such as lemon juice or white vinegar).